Putting a bottle or carton in the blue bin feels virtuous. We’ve been taught that recycling is the way to help the planet. But the truth is that recycling has largely been a feel-good myth that distracts us from more effective action. Decades into the recycling experiment, the numbers tell a stark story: only about 9% of all plastic ever produced has actually been recycled. The rest has been landfilled, incinerated, or simply littered into the environment. What about materials like glass or aluminum? They do have higher recycling rates and they don’t degrade as quickly as plastic. But even “successful” recycling comes with a huge energy and carbon cost.

To truly tackle waste and pollution, we must shift our focus to reuse and reduction. The most sustainable package isn’t the one you recycle – it’s the one you never discard in the first place.

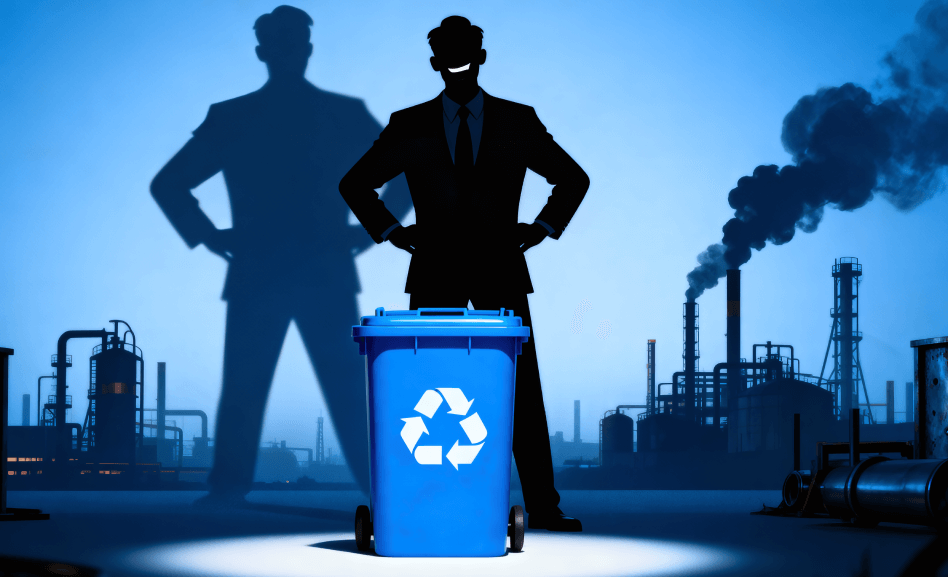

How Big Oil Sold the Recycling Myth

It might surprise you to learn that the ubiquitous chasing-arrows recycling symbol was not created by environmentalists. It was created by the plastics industry in the 1980s as a clever PR move. At the time, public concern about plastic pollution was growing, and lawmakers were considering bans on certain single-use plastics. In response, the major oil and chemical companies orchestrated a massive campaign to convince the public that recycling would solve the plastic waste problem. Internal industry documents from the 1970s have since revealed that executives knew all along recycling wouldn’t keep up with plastic production – one 1974 report stated there was “serious doubt” plastic recycling could ever be economically viable at scale.

A key part of this strategy was the introduction of the Resin Identification Code on plastics in 1988 – those little numbers 1 through 7 inside a triangle of arrows. This symbol closely mimics the recycling logo, leading 92% of Americans to believe it means a product is recyclable. In reality, only plastics #1 and #2 (like soda bottles and milk jugs) are commonly recyclable; most of the others (types #3–7) are not accepted by recycling facilities and end up in landfills.

Why Recycling Keeps Failing (It’s Not Your Fault)

Even when done earnestly, conventional recycling is fighting an uphill battle against basic economics and physics. The system is riddled with challenges that often make it ineffective by design:

- Contamination: Recycling isn’t as simple as melting down a clean water bottle. If recyclables are mixed with food residue or non-recyclables, the whole batch can be ruined. (Think of a greasy pizza box seeping oil into a load of paper recycling – that entire load may be sent to trash.)

- Market Economics: The premise of recycling assumes there’s a manufacturer eager to use the recycled material. But often, new “virgin” material is cheaper. When oil prices are low, brand-new plastic made from petroleum undercuts the price of recycled plastic. Recyclers then have no one to sell to. And even when recyclables are collected, they may be “downcycled” into lower-grade products. For example, a plastic bottle typically won’t become a new bottle (food safety rules and polymer degradation make that difficult). Instead it might be turned into fiber for carpets or clothing, or plastic lumber for a park bench . Those products are useful, but usually can’t be recycled again.

- Energy and Emissions: Recycling is often touted as a way to save energy. But the energy required to complete the recycling process can be significant. Fleet trucks to collect curbside bins burn diesel. Sorting facilities and processing plants consume electricity and heat. By the time you’ve taken a used plastic item through collection, baling, shipping (sometimes across oceans), re-melting, and remanufacturing, you’ve expended a lot of energy – and created not-insignificant carbon emissions. One study noted that when you account for collection and sorting inefficiencies, the carbon footprint of recycling certain plastics can be nearly as high as making new plastic. And if a batch is contaminated and ends up landfilled anyway, all that collection energy was wasted.

- Capacity Limits: The complexity of modern packaging has also outpaced our recycling infrastructure. Many common items – coffee cups lined with plastic, black-dyed plastics, foam containers – are not recyclable with current technology or at economic cost. Yet companies still put recycling symbols on them, further misleading consumers. Even for the straightforward stuff like bottles and cans, recycling facilities have finite capacity. The world now produces 430 million tons of plastic a year (and rising); our ability to collect and reprocess a meaningful fraction of that has never kept up.

The takeaway here is not that recycling is pointless. Proper recycling still has environmental benefits over outright trashing, especially for materials like metals, paper, and glass. The problem is that recycling has been asked to do too much – to paper over a fundamentally unsustainable flood of disposable goods.

The Psychological Trap: Recycling as a Cop-Out

Perhaps the most insidious impact of the recycling myth is how it’s warped our mindset. We’ve been encouraged to see recycling as action, when it might actually be a form of inaction – or at least a less effective action. Psychologists talk about “moral licensing” or the rebound effect, where doing something “good” in one area (like recycling) can make us feel justified in being less responsible in another. When it comes to waste, this means people might consume more single-use products precisely because they assume recycling absolves them of guilt.

Another study noted that after communities adopted recycling programs, there wasn’t a corresponding drop in waste generation; in some cases overall consumption actually rose, as people bought disposables with the confidence that they’d be recycled later. It’s like ordering a double bacon cheeseburger and a large fries… but feeling virtuous because you got a diet soda. The “diet soda” in our case is recycling – a token gesture that eases the conscience, while the real issue (our appetite for single-use stuff) goes unaddressed.

Corporations understood this psychological dynamic and capitalized on it. By promoting recycling (and putting recycling logos on everything), they effectively redirected our environmental anxieties into a narrow behavior that doesn’t threaten their business model. We’re less likely to demand bans on plastic packaging or to buy less when we believe the solution is as simple as sorting our trash.

Why Reuse Changes Everything

Recycling fights to mitigate the back end of a product’s life. Reuse tackles the front end by avoiding the waste altogether. It’s a simple concept with radical implications: the greenest packaging is no new packaging at all. Every time you refill a container or use a product again, you eliminate the need to manufacture a new one and prevent one more item from becoming waste. This is why the familiar mantra “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” is actually in order of importance – and why reuse is a far more powerful lever for sustainability than recycling.

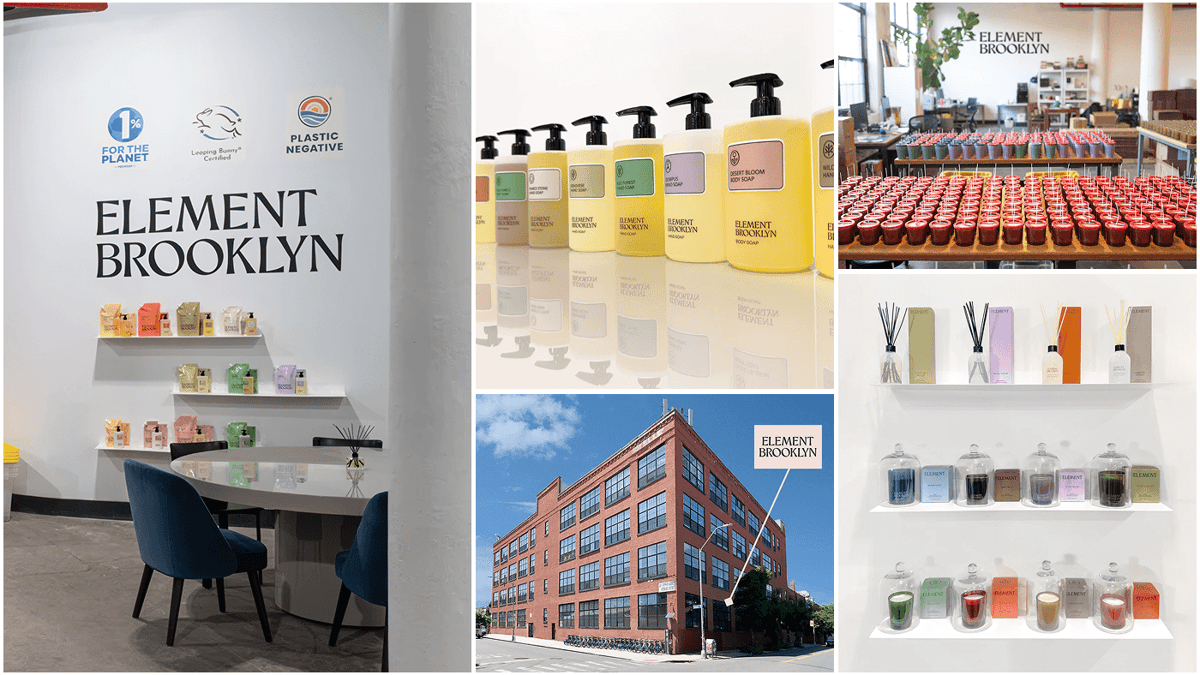

At Element Brooklyn, this principle is at the core of our business. We offer our hand soaps, creams, and hair care products in refill pouches so customers can reuse their original bottles. Each of our refill pouches uses roughly 85% less plastic than a standard bottled product. Beyond pouches, we’re pushing toward closed-loop reuse systems. We’ve partnered with forward-thinking refill shops (or “refilleries”) like Maison Jar in Brooklyn and re_grocery in Los Angeles to eliminate disposable packaging entirely.

The impact of reuse is both intuitive and astonishing when scaled. By one estimate, reusing a single glass jar (for shopping bulk foods, for example) 50 times has 50 times the benefit of recycling it once. Since our launch, Element Brooklyn’s customers have prevented hundreds of thousands of plastic bottles from being produced by switching to our refill model.

What Real Change Looks Like

Here are a few promising directions and how they’re proving more effective than the old recycling status quo:

- Deposit Return Programs – Remember returning soda bottles for a nickel? That concept works incredibly well when the deposit is high enough. Take Germany, which operates perhaps the world’s most successful deposit-return scheme: customers pay an extra €0.25 on single-use drink bottles and cans, and get it back when they return them. This system achieves a 98% return rate for eligible beverage containers.

- Refill Infrastructure in Public Spaces – One reason disposable plastic bottles proliferated is that we designed cities and lifestyles around them. But cities can flip the script. Paris, for example, has installed over a thousand free public water fountains (including some that dispense sparkling water!) to encourage people to refill bottles instead of buying disposable water bottles . They’ve even enrolled hundreds of shops and cafes in a program where you can pop in and refill your bottle for free, no purchase needed . This kind of infrastructure directly eliminates the need for single-use bottles.

- Bans & Mandates for Reusable Packaging – Governments are stepping in to push the system toward reuse. Chile’s ban on single-use plastics in dining establishments is one example, effectively forcing a switch to durable tableware and takeaway containers that can be washed (or to compostable materials). The EU is going further by setting quantitative targets: by 2030, 10% of take-away food and drink sales must be in reusable packaging, scaling up to higher percentages in following years . They’re also banning certain unnecessary single-use packaging outright (like those tiny hotel toiletry bottles, and disposable packaging for sit-down restaurant meals).

Will recycling have a place in a truly sustainable future? Yes – but a more modest one. We will likely always recycle metals, paper, and glass to some extent, and even plastics will need recycling in closed-loop systems for durable goods. But recycling should be the last resort after we’ve reduced and reused to the fullest extent.

What You Can Do

Here are some tangible steps that focus on efforts that actually move the needle:

- Choose Reuse First: Make reusable containers and products a staple in your life. Carry a refillable water bottle and coffee cup. Use cloth shopping bags. Opt for products that come in refillable packaging or no packaging.

- Support Refill and Zero-Waste Shops: These businesses are pioneers in building a reuse economy. Refilleries and zero-waste grocery stores allow you to bring your own jars or rent containers to buy everything from detergents to dry foods. By shopping at these places, you vote with your wallet for a refillable future.

- Demand Better from Companies: Corporations pay attention to consumer demand and feedback. Let your favorite brands know that recycling isn’t enough – you want reusable or truly sustainable packaging. If a product you love is sold in a wasteful package, ask the company if they’ve considered a refill or take-back program.

- Resist “Recycle Guilt”: Finally, cut yourself some slack. The waste crisis can’t be solved by individual purity or 100% perfection. Despite your best efforts, you will sometimes have waste to throw out – that’s okay, and it’s often not within your immediate control. The key is to not let the existence of waste demoralize you or lull you back into complacency.

It’s time to face a hard truth: Recycling isn’t “saving” the planet – at least not on its own. In fact, as currently practiced, it has often served to save companies from scrutiny, by giving consumers the illusion that everything will work out after disposal. Meanwhile, environmental damage from overproduction and waste has continued to mount. Plastic clogs our oceans and landfills, microplastics invade our food and bodies, and carbon emissions from manufacturing surge on. We don’t lack recycling facilities – we lack systemic restraint on making so much unnecessary stuff. The blue bin was a step, but not the destination. It’s time to move beyond it. Recycling, as we’ve known it, was a story we were told to keep us consuming. Reuse is a story we write by changing how we live. And in that story, we aren’t just feel-good participants – we’re the heroes actually making a difference.